Beginner’s Guide to Filming a Documentary on a Smartphone

Documentary filmmaker David Tamés suggests filmmakers “should not worry too much about gear on your first project”.

“The intimacy and rapport you develop with your subject is more important at this point than mastering technical craft. Consider shooting your first video with a smartphone or an easy-to-use consumer camcorder to keep things simple. If you already own a video camera that is capable of shooting high definition video, use that. When you’re starting out, the best camera is the one you have.” David Tamés

Sound is still very important. Shooting a documentary, I would say getting good audio is possibly even more important than a narrative fiction film. With actors, there’s always the possibility of dubbing the voice after filming. This is impossible to do with your interview subjects or subjects recorded during spontaneous moments “on the fly”.

8 Tips on How to Shoot a Documentary with a Smartphone

Recently, I shot a documentary using smartphones.

I wrote, shot and edited the whole project on my own. So if I can do it, you can do it.

My documentary was about the making of a short horror film, shot on an iPhone 13 Pro Max by smartphone filmmaker, Johnny Kinch. Well, I could blabber on about it or I can just show you the trailer. So here it is:

Members on my Patreon watch the whole documentary (which is about 36 minutes long) when it’s released on August 2nd. It’s only $5 and you can cancel any time. And you’ll get 4 smartphone filmmaking ebooks to download as well as all the other stuff available to members (see below).

When we see those Apple-funded “shot on iPhone” videos, a lot of people comment: “well they had a huge budget, tons of crew, lighting and so it’s not just shot with the iPhone. Most of us don’t have access to that kind of kit”.

Well, I can tell you that for my doc I pretty much used nothing but a smartphone. I used my iPhone for the behind the scenes and my Samsung for the train footage. In the shot of me looking out the window, I’m actually holding the Samsung against the back of the seat in front of me and pretending that I’m deep in thought, as I gaze out of the window.

In fact, I’m just hoping that I’m framed ok and that I will have enough footage when I edit.

The only time I used extra equipment was for the interview. For that I used a Rode Wireless GO II mic and a tripod (which I actually borrowed from Johnny). The only expense for this video was the 2 train tickets to Johnny’s house. And as I used the train for filming, I got double the value – travel and location cost combined!

So here’s my 8 tips for shooting a documentary with your smartphone.

1. Check your Footage

When I first started filming, I was just using the native camera on the iPhone 12 Pro Max. We went up into the attic where they were filming and I started getting some shots. The light was pretty low and I could straightaway see the footage was coming out pretty noisy.

So I played back what I’d got to check how it was coming out. And yes, it was horribly noisy, even when I pulled down the exposure.

If I’d kept filming without checking what I was getting, I would have ended up with tons of noisy footage. But once I saw the problem, I was able to act to fix it before I shot any more footage.

So don’t just film all day and then check what you have. Keep checking as you are filming, when you get the opportunity. It might save you a lot of wasted time in the long run.

So how did I fix this problem? I used a camera app.

2. Use a Camera App

I quickly booted up FiLMiC Pro and used the manual controls to bring down the ISO. And even though the exposure looked about the same level, I got much less noise in the image.

So, if you’re filming with an iPhone especially, I really think using a camera app which gives you manual control is absolutely essential. Particularly for low light situations.

Once we were filming outside, I actually went back to using the native camera app. The reason being that I believe the iPhone native gives you a wider dynamic range using the native app.

The same goes for android phones with Pro mode. Pro mode gives you manual control but reduces dynamic range. So a general rule would be to use manual control in low light conditions and the native app in brighter conditions.

Whichever you use, you will usually want to lock exposure. That said, I don’t always lock it. And that’s my next tip for shooting a documentary.

3. Balance Spontaneity with Control

Most filmmaking tutorials will tell you you need to lock exposure, focus and white balance to create more professional looking shots. The problem is that while you’re busy navigating the settings in FiLMiC Pro, if something dramatic happens you’ll probably miss it.

How much camera control you use depends a lot on how you are filming your documentary. If your documentary is very much pre-planned, with lots of interviews for example, then you can afford to spend time getting the camera settings right before you start filming.

But I was filming what they call a fly-on-the-wall documentary. Which meant I was capturing real life as it happened. For that reason, I often used auto exposure and focus.

If events are happening too quickly for you to keep setting shutter speed and ISO and so on, then it’s ok to use the camera in auto. When something spontaneous is happening, your audience will understand and forgive a slightly rougher looking image.

4. Avoid a Roving Camera

When you are filming events which are happening spontaneously it’s a good idea to keep your camera movement limited. For shooting a doc, a motionless camera has a number of advantages.

Firstly, if you are using auto settings in the camera, a motionless camera will cause less problems than a moving one. That’s because things like exposure, focus and white balance changes become more obvious when you move the camera.

Secondly, when you don’t know what’s going to happen in front of the camera, keeping the camera still means you are less likely to miss something. Or you might ruin footage of a key event because just as that unrepeatable moment happened you moved the camera.

When you’re filming people doing whatever it is they’re doing, let them do the work for you. It’s your job to just quietly observe and only move the camera if you have to to follow the main action. Of course, I’m not talking about small movements here, rather I’m suggesting you avoid complete changes of framing.

There will of course be times when a camera movement is needed to follow the action.

5. Use an External Mic

My tip number 5 is to use an external mic to record the audio. And that’s particularly true for interviews.

I really recommend using a clip on mic of some kind. You can get these mini shotgun mics that clip to your smartphone, but I find they only add about 5% improvement, especially with newer or more expensive smartphones which actually have really very good inbuilt mics.

Bigger shotgun mics like the Rode VideoMic NTG are much better, but for an interview I would still suggest a clip on mic.

For this documentary interview, I used the Rode Wireless GO II system. You can connect it directly to the smartphone you’re using to record the interview. But I actually just used the transmitter as a standalone recorder with a Rode Lavalier II attached.

When I edit the video in Adobe Premiere, it’s very easy to sync the Rode audio with the smartphone audio.

Spontaneity vs Audio Quality

Having said you should use an external mic, again you also have to weigh up spontaneity vs quality. This spontaneity vs quality question is central to your process when shooting a doc.

Johnny is a great subject for a documentary because he’s never short of words. As soon as I met him, he started talking about the project as well as his difficult life story. You have to decide whether to just start filming and capture the moment or whether you need better quality audio, which might mean losing some of that spontaneity.

So, for most of the shots, I decided to just start recording with nothing but the internal mic of the iPhone 12 Pro Max.

When you are shooting an interview, it’s not a live situation. The subject is ready for the interview and expects to be mic’d up. But when things are happening spontaneously, asking everyone to wait while you prepare audio equipment could mean you losing the spontaneity of the moment. It can also make people feel more self conscious.

The beauty of filming with a smartphone is that everyone is used to it. Most of the time, they hardly even notice. So it’s very easy to become a neutral observer, which is what you really want for the documentary. As a filmmaker, you hope to be as invisible as possible, so that people feel comfortable being themselves.

6. Log Everything

Usually when you’re shooting a documentary, you’ll end up with loads and loads of footage. So it’s important to go through everything and make a log of key moments.

For example, the interview I did with Johnny was over 1 hour long. Before I started editing, I went through the interview, adding markers in Adobe Premiere. Then, in a Google doc, I made a note of key subjects that he mentions and the time he mentions them.

When I came to edit, this made it easy to find the parts I wanted.

7. Use Storytelling

A documentary isn’t just about shooting what happens and then cutting it all together in the order that it happened. It’s still up to you to tell a great story and it all comes down to how you edit things together, what you show and what you don’t show, what you reveal and when you reveal it.

When people tell you about their lives at length, they probably won’t tell you things in an exact chronology. We tend to jump around in our life’s timelines, as we remember things. And it’s probably a good idea not to interrupt this process when you’re interviewing someone as you will get a more natural interview.

And that’s another reason why logging the interview is important. Now you can move things around to fit the structure you want for your documentary. For example, an interview subject might reveal certain events early on when in your doc you don’t want to reveal this event until later.

This is where your storytelling skills come in. You can tell the story the way you feel works best by rearranging the order of what was said.

8. Get B Roll

Apart from filming what’s going on, make sure to capture some B roll shots as well. When I say B roll I mean subjects which are aside from the main action. These B roll shots really help you out when you are editing. They give you somewhere to cut to as well as give you more variety of shots in your final video.

For example, the stuff I filmed on the train to Johnny’s place. I got some shots out of the window too and a shot walking along the platform. This was all useful footage to place under a voice over I wrote to introduce each section of the doc as well as give some final thoughts.

When you are filming, there will be low moments, when not much is happening with the subject of the documentary. Use that time to grab some close ups of interesting details. These will make the doc more visually interesting, as well as reflect on the theme of the video.

Smartphone Documentary Audio

You can actually get away with the inbuilt smartphone microphone, especially with later, high-end phones. However, you need to be a minimum of about 1 meter away from the subject. The good news is that smartphones have wide lenses, forcing you to get in close.

The closer you get the microphone to the subject’s mouth, the clearer the sound: less background noise, less reflections from nearby surfaces (bare walls, ceilings and floors are the worst).

Preferably you will use some kind of external microphone. Good quality clip on mics can be bought for as little as $15.

It’s always useful to monitor your sound as you are recording. There can be audio issues you don’t notice without headphones on. For example, we recently filmed an interview and didn’t notice the subjects hair was brushing over the microphone while she spoke.

The problem is, if you have a mic attached to smartphone, it’s usually taking up the headphone socket. There are solutions however. For example, the IK Multimedia iRig Lavalier allows you to connect both headphones and a second iRig Mic Lav.

Note: try to use headphones which block out as much background noise as possible. You’ll need over-the-ear headphones or sound-isolating earbuds.

You might want to think about adding an external recorder. For example, the Roland R-07-RD Portable Field Recorder. You can even remotely control this recorder from your smartphone.

Alternatively, I have been using a Zoom H4N for 10 years and it’s never let me down. This recorder has stereo mics inbuilt so it can act as a portable microphone set up too. You can hide it in a pocket or around the shooting location – just leave it recording as you shoot.

Recording outside? Watch out for wind blowing against the mic. Use a windjammer.

Smartphone Stabilisation

I’ve already listed a bunch stabilisation kit:

Release forms for Docs

Depending on where you are filming, you might need to get anyone appearing in your film to sign a release form. David Tamés has a free PDF of suggested release forms. You will have to check for yourself if they cover your needs legally.

Smartphone Camera app

To get more manual control over your phone’s camera, you can use a camera app such as FiLMiC Pro.

I will always encourage any smartphone filmmaker to minimise the need to tinker with technology, when you could be being creative instead. However, the joy of such freedom while shooting can turn sour during post-production – this is when we receive our reality check.

Using a camera app, you can film with correct white balance and locked exposure. This will result in a more joyful, less hair tearing, editing and colouring process once you’ve imported the footage into your chosen editing system.

Over exposed or under exposed video results in the lost highlight or shadow details. So using a camera app and learning how to get the best results with it will save you a lot of headaches later.

Of course, there’s a learning process involved. There’s also a need for a healthy balance between spontaneity and technical perfection. Especially with documentary – don’t lose that perfect, dramatic moment while you tinker with the white balance.

Why a smartphone is perfect for shooting documentaries

Depends which kind of documentary you’re shooting, of course. If it’s mostly studio-based interviews cut with stock footage or stills, then not so much. But an out-in-the-field project, where you’re trying to convey the feeling of being there; where you’re trying to be spontaneous and catch your subjects unaware of being filmed as much as possible – then the smartphone has a distinct advantage.

Take the recent festival hit documentary, Saudi Runaway, shot using a couple of smartphones with the subject doing the filming. All this then cut together to create an edge-of-the-seat thriller.

Everyone (unless you are filming an Amazonian tribe) is so used to seeing people holding and using smartphones, you can be as anonymous as it’s possible to be with a camera in your hand. Smartphones are designed for the specific purpose of speed and ease of use. If you are used to using your smartphone camera in daily life, you can go from reading an email to shooting in 10 seconds.

Feeling of Being There

Richard Leacock was a British documentary filmmaker who dedicated his career to creating the feeling of “being there” in his films. As he started shooting before the 2nd World War, you can image the struggles he went through to achieve this.

This is a great quote from Leacock describing the difficulty of filming subjects, whilst keeping it real and natural.:

“In general, when you are making a film you are in a situation where something you find significant is going on. Usually the people you are filming want to help you get what they think you want to get; often as a way of getting rid of you. And this can be fatal because they are then second-guessing you and can end up destroying the possibility of achieving your aim.

“I remember Bob Drew and I coming into the lawyer’s office when we were making THE CHAIR. He asked what he could do for us, we said, “nothing”, put our equipment in a corner and went out for coffee. A little later we came back in and he was back at work doing what had to be done, having decided that we were nuts. We kept our distance and started filming as he picked up his phone…”

Leacock was working in the days he had no choice but to use large, clumsy 35mm or 16mm cameras. When audio equipment weighed 70 pounds or more and when trying to achieve the intimate direct cinema approach was almost impossible.

You can read a full extract of his adventures and struggles here. What’s interesting is that he describes how even once the equipment was available to film sensitively and discreetly, filmmakers would still barge in and clumsily create artificiality – because that was what they had been taught was “professional” filmmaking.

Although Leacock was happily using digital cameras and editing kit right up until his death, as he died in 2011 he didn’t quite make it to experience our 4K smartphone filmmaker landscape. We can only imagine he would have loved to have shot with a phone.

“Knowing just how long one can make a scene last is already montage, just as thinking about transitions is part of the problem of shooting.” Jean-Luc Godard, Montage mon bon souci (1956)

With documentary the quest is for observation footage

Even with our interview-based doc, you will raise the level of the work with some interesting observation video to cut with them. If not, you will simply be presenting a series of talking heads. To stop your audience growing tired of talking heads include some kind of visual storytelling.

Because, if you really aren’t going to include a visual story, then you might as well make it a podcast or radio doc.

Filming documentary footage is different to filming narrative fiction – it’s a lot more ninja.

To hunt… means to release yourself from rational images of what something “means” and to be concerned only that it “is.” And then to recognise that things exist only insofar as they can be related to other things. These relationships— fresh drops of moisture on top of rocks at a river crossing and a raven’s distant voice — become patterns. The patterns are always in motion…” Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams (1986)

Look, you’ve got the most versatile, lightweight, least scary camera ever invented, right in your pocket. If you can’t get intimate, revealing, shocking, real, surprising, private, emotional footage with a smartphone camera, then you never will.

So, whilst some filmmakers are out there struggling to get anything raw because of all the kit they have to set up before they can start filming, make your advantage tell. Get footage you could never have got with a regular camera. Saudi Runaway is the perfect example of this principle.

You are part of the story

There’s no such thing as a truly objective documentary. That’s because a documentary is so often about the relationship between the filmmaker and the subject. However, it’s often in a filmmaker’s nature to hide behind their equipment and their filmmaking job.

Through this fear, perhaps under the misunderstanding that they want to be objective and influence the subject as little as possible, the filmmaker separates themselves from the subject. They draw a deliberate boundary: I’m the filmmaker over here – you are the subject over there.

If you do this, you are casting aside the biggest advantage you have as a smartphone documentary maker.

“Early in its history cinema discovered the possibility of calling attention to persons and parts of persons and objects; but it is equally a possibility of the medium not to call attention to them but, rather, to let the world happen, to let its parts draw attention to themselves according to their natural weight. This possibility is less explored than its opposite.” Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed (1971)

The more you become subsumed into the world you are documenting, the more true and revealing the footage you will acquire. and with a smartphone, this process is so much easier.

Frame, focus, wait…

Be thoughtful about how you move your camera. The temptation is to swing left and right, following the subject here and there, searching for interesting images. We have a kind of inbuilt restlessness which drives us to search for better and better, or to avoid any second of boredom.

But when you return home with this footage, as a result of this “garden hose” type approach you will find yourself scrolling through take after take, desperate for moments of stillness.

If the subject is moving, why not allow them to move in and out of frame? This isn’t natural to us, as we normally move our heads to follow the action. However, it’s not a cinematic experience to have this motion forced upon us as a viewer.

The moving image becomes more poetic when the frame is still and we allow reality to take place without our interference. Now the view is more artful, more composed, allowing the viewer to dwell in their own thoughts.

Of course, you can still move the camera. But make those movements precise and thought out. Even if you are shooting on the fly, you can still develop a sense of where your view starts and where and how it comes to rest. And you can do this without wildly searching for something to focus on.

The more you shoot, the more instinctive this will become.

Smartphone Video – Beginner to Advanced

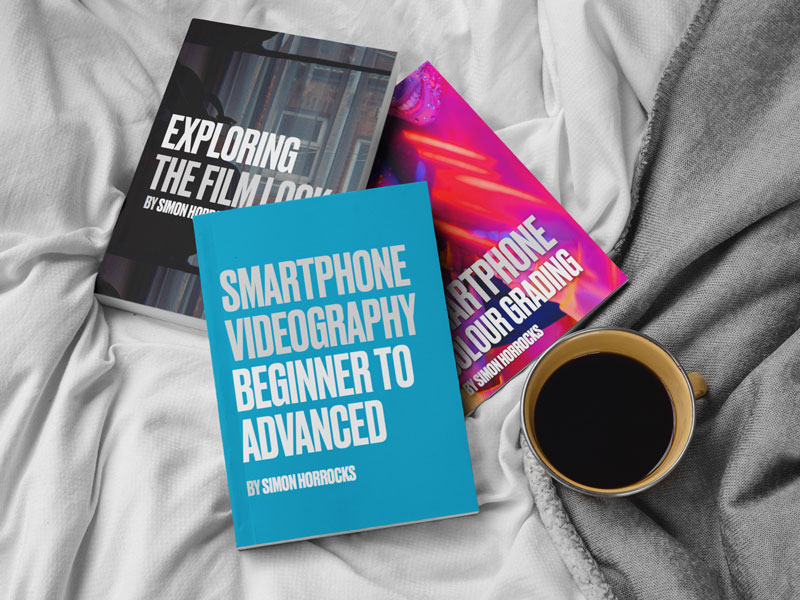

If you want to know more about smartphone filmmaking, my book Smartphone Videography – Beginners to Advanced is now available to download for members on Patreon. The book is 170 pages long and covers essential smartphone filmmaking topics:

Things like how to get the perfect exposure, when to use manual control, which codecs to use, HDR, how to use frame rates, lenses, shot types, stabilisation and much more. There’s also my Exploring the Film Look Guide as well as Smartphone Colour Grading.

Members can also access all 5 episodes of our smartphone shot Silent Eye series, with accompanying screenplays and making of podcasts. There’s other materials too and I will be adding more in the future.

If you want to join me there, follow this link.

Simon Horrocks

Simon Horrocks is a screenwriter & filmmaker. His debut feature THIRD CONTACT was shot on a consumer camcorder and premiered at the BFI IMAX in 2013. His shot-on-smartphones sci-fi series SILENT EYE featured on Amazon Prime. He now runs a popular Patreon page which offers online courses for beginners, customised tips and more: www.patreon.com/SilentEye

Thank you for sharing such a important information.

Thank you so much for all of this encouraging information!

I’m a in patient in a hospital been there 3 years and want to do a documentary i haven’t done this before and I had a number of email asking me to

Do one I want to change my life and want to raise awareness