Shutter Speed for Video – the Basics Explained

Shutter speed can have a dramatic impact on the appearance of your video. Below is a gif showing the difference to a series of still images. Essentially, the longer the shutter is open, the more light is allowed through the shutter. At the same time, any movement taking place in the frame becomes increasingly blurred.

I talked a bit about this in the post on frame rates. Specifically, how shutter speed was used to get the detailed explosion effect in Saving Private Ryan.

The History

Most of the manual settings available to use on our digital camera originated when cameras were very much mechanical devices. In the very early days of photography, a camera’s shutter was the lens cap. The photographer would remove the lens cap allowing light through the lens, then replace the cap after the required exposure time had elapsed.

To give you an idea of how far we have come, the oldest surviving photograph is now thought to have had an exposure time of several days. This photograph was taken in the year 1826 or 1827 – approaching 200 years ago!

The photograph below is the oldest existing photo containing people. Named the “Boulevard du Temple“, it is a daguerreotype made by Louis Daguerre in 1838. The exposure time was so long, none of the traffic or pedestrians remained in the frame long enough to leave a mark. Except for 2 men – one having his shoes polished by the other.

The material reacting to the light to create the image reacted so slowly, in these early years, that the “shutter” speed had to be extremely slow to allow enough light. So slow that moving objects were impossible to capture.

Built-in Shutters

The very first shutters were separate accessories. Built-in shutters became common by the end of the 19th century. George Eastman developed his first camera, which he called the “Kodak,” in 1888. It was a very simple box camera with a fixed-focus lens and single shutter speed. Much like smartphone cameras today, this Kodak camera was designed to be simple to use. Thus the camera appealed to the masses and Eastman made his fortune.

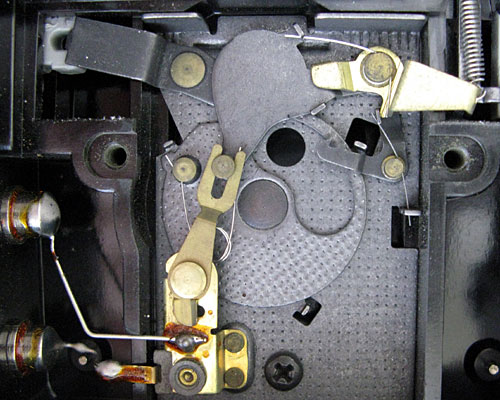

Here’s an old box camera equipped with a rotary shutter…

Cut to: the present day. We now have DSLR cameras which offer shutter speeds of 1/16000 of a second. This is only possible due to the modern development of highly sensitive light sensors, which need far less light.

Shutter speed in film

Motion picture cameras used in traditional film cinematography employ a mechanical rotating shutter. The shutter rotation is synchronized with film being pulled through the gate, hence shutter speed is a function of the frame rate and shutter angle.

With a traditional shutter angle of 180°, film is exposed for 1⁄48 second at 24 fps. This is why this frame rate + shutter speed combo is often recommended for video shooters trying to emulate the “film look”.

One difference between film and stills photography, is the the need to capture a number of frames within a limited amount of time. So, for your smartphone videos, your shutter speed is dictated by your frame rate, to a certain degree.

Electronic shutter

Smartphone cameras have electronic shutters, rather than mechanical ones.

“Essentially, your smartphone will tell the sensor to record your scene for a given time, recorded from top to bottom. While this is quite good for saving weight, there are tradeoffs. For example, if you shoot a fast-moving object, the sensor will record it at different points in time (due to the readout speed) skewing the object in your photo.” Chris Thomas

Faster shutter speed, less motion blur

There is often some confusion about what people have started to call the “180 degree rule”, sometimes confusing it with the 180 degree rule when choosing angles for a scene. When it comes to digital filmmaking, there is no physical shutter, so therefore no 180 degree angle.

Actually, with digital filmmaking it’s rather simple. The longer the shutter is open (slower speed) the more motion blur you will get. Traditionally, the shutter speed for 24fps was 1/48th using film cameras. So if you want to mimic that look, a shutter speed of 24fps = 1/48th or 25fps = 1/50th is about right.

But the faster the shutter speed is above 1/50th, the less motion blur you will get and the less your footage will look like film.

The video below is a great demonstration of the the different combinations of shutters speed and frame rates:

Artificial light flicker

After filming a scene using artificial lights, or which include artificial lights within the frame, you might notice those lights flickering, unnaturally. This is due to the artificial lights flickering at a rate determined by the mains supply of the country you are in.

When your shutter speed and frame rate are “out of sync” with this artificial light flicker, your camera will capture the light at different strengths. This creates an annoying pulsating effect.

This video is a good demonstration of what it looks like, but he doesn’t really explain what’s happening:

The frequency of AC currents differs depending where you are. In much of North and South America it’s 60 Hz and in Europe, Africa and Asia, it’s 50Hz. So the simple solution is – try to sync your shutter speed to the rate of the local mains power.

For example, I film in Europe. So I found shooting at 24 fps 1/48th creates that flicker effect with artificial light. However, if I change to 25 fps and 1/50th, the problem is solved.

See, the 50Hz AC current is now “in tune” with my 25 fps and 1/50th shutter speed. In a 60 Hz AC area, you’ll need to shoot at 30, 60 or 120 fps. This way, each frame gets the same number of light “pulses”.

Consider Supporting us on Patreon.

We have a limited offer! Be listed on our exclusive filmmaker network page and submit any films to our festival free.

Eager to learn more?

Join our weekly newsletter featuring inspiring stories, no-budget filmmaking tips and comprehensive equipment reviews to help you turn your film projects into reality!

Simon Horrocks

Simon Horrocks is a screenwriter & filmmaker. His debut feature THIRD CONTACT was shot on a consumer camcorder and premiered at the BFI IMAX in 2013. His shot-on-smartphones sci-fi series SILENT EYE featured on Amazon Prime. He now runs a popular Patreon page which offers online courses for beginners, customised tips and more: www.patreon.com/SilentEye