Basic Video Editing Tips

How important is editing to the video making process? Actors often say they owe their great performance in part to the amazing work of a skilled editor. That’s because skillful editing can turn something ordinary into something extraordinary.

Imagine each shot in a sequence is like a note in a music score…

As I am sure you are aware (and have experienced yourself on many occasions), music notes can be arranged in such a way that it transports you to another world… Or they can be lumped together in such an horrible, discordant way the music gives you a headache.

So, no surprise editing and music are closely connected. They both use rhythm in a powerful way, for example. And often professional editors will edit to the music underscore: lay the music track down and then start placing the shots, using the pacing and emotion of the music to guide the selection.

These tips have been shared before, but this is my take on them, based on my own experience.

Tip 1: Build Don’t Whittle

It’s tempting to collect all your shots and throw them onto the timeline, then start chopping away the bad stuff to leave the average to great stuff remaining. I think you are setting yourself problems by using this method, as your brain will get used to seeing certain shots and grow attached to them, even though they might not be the best.

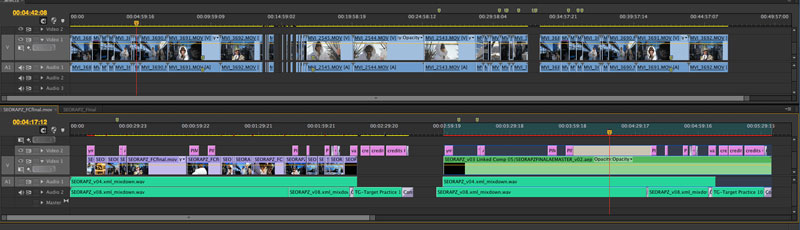

Instead, go through your footage and select the most exciting or useful bits. In Adobe Premiere (and most other editing software) you can mark in and out points before you place the shot on the timeline. Only select the best bits before placing them on the timeline.

If you find you are missing something, then you can go back and see if one of your less exciting shots will work to fill the gap.

“Build from the ground up with only your best shots.” Sven Pape

The value of a shot increases by repetition, tricking you into thinking it needs to be there. You see, one of the challenges of editing is to keep your mind as fresh as possible. So by only selecting the best stuff, you are saving your brain from overwork and the risk of tiredness clouding your judgement.

Tip 2: Match Image and Audio

Sometimes a contrasting image and audio combination can work, perhaps for comedy effect. However, most of the time an editor’s job is to combine audio and video in a harmonious way.

An obvious example of a contrast would be a slowly panning shot of a cityscape while the narrator is talking about running across an open field. The two would conflict with each other in the audience’s mind (of course, you might want that).

Again, your aim is for music and image to combine rhythmically, atmospherically and thematically. I talked about how music and image combine well in this article.

As an editor, the hours you spend tweaking, shaving frames here and there, adjusting the shot timing to the background audio (or visa versa), colouring… everything, are spent trying to perfect a work where all the elements work together. Like a sculptor, with the video and audio your clay, you are bit by bit shaping this thing into an impressive whole.

Tip 3: Arrive Late and Leave Early

Really, this just emphasises all the above. To keep your editing tight, make sure you start the shot at the last possible moment and end the shot as soon as you can. Well, this is really a general rule to help you avoid losing the interest of your audience – which is one of the most common beginner mistakes.

You think your movie needs to be 2 hours long to tell your story without leaving anything out? OK, count to 10 seconds in your head. 10 seconds is really a long time, isn’t it? In video terms you can say a lot in that time – much more than many people realise.

The problem with editing (and a lot of other creative skills) is self-indulgence. You get narcissistically obsessed with your own creation and become so attached to it you can’t bear to cut it down to a more “efficient” experience.

I enjoy Bergman and Tarkovsky and all the other filmmakers who like to include drawn out shots and sequences. Hey, I even like Gus Van Sant’s Gerry which has 5 minute shots of 2 guys walking silently in a desert…

Well, I’d already read about the film before watching so prepared my mind for these long shots. The thing is, this is a deliberate creative choice by the filmmaker. It’s about 2 guys lost in a desert, slowly dying. So the film really expresses that mood by forcing the audience to sit through a cinematic simulation of how it must have felt.

So, if you are including long takes in your film, make sure it is justified – not just because you got lost in the editing desert and your mind gave up hope of ever reaching safety…

Having said that, sometimes I have had the opposite problem. I’ve cut a short film too tight and the whole thing felt like a long trailer. I had to go through adding some pauses and extra space to allow the film to “breathe”. If you go too fast the audience might not be able to keep up.

Alfonso García has been making smartphone films for a few years and has developed an ultra fast editing style. He really creates a frantic, tense experience. Warning: the following short is a horror film:

Tip 4: Hey, look at this!

So, what is the point of editing anyway? Essentially, you are telling the audience what they need to see to follow the story.

“Every time you go to a closeup, the audience knows subconsciously that you’ve made an editorial decision. You’ve said, ‘Look at this; this is important.’” David Fincher, director of Seven, The Game, Fight Club, The Social Network

The director’s job is to make sure you get all the footage the editor needs to bring her vision to life. So the director (and the screenwriter) will be thinking about ‘which story beats do we need to show the audience and in what order’? Then the editor takes all the pieces and puts the jigsaw puzzle together.

So, in essence, the writer, director and editor are constructing a visual sequence which goes, “look at this, now this, now this, and then this…” and so on.

Although this might seem obvious, it’s a good thing to consider when you are editing. As someone who watches a lot of films by new filmmakers as part of my job as festival director, I can see many films would benefit from someone asking “Why am I showing the audience this?”

Ask yourself what every shot is for and this will help you to weed out the shots or bits of shots which are surplus to requirements.

Tip 5: Don’t Be A Slave to Tip 4

If you methodically take your audience beat by beat through the story, it can come across as a bit heavy handed and crude. Imagine a novel goes, “This happened, then this happened, then this happened…” and so on all the way through. After a reading a few pages, you would get tired. In a way, this is how a child might tell you about an experience they had.

If you want to develop a more mature, sophisticated editing style, you need to be more creative – think about when not to show things.

One good example is when editing dialogue scenes. The most obvious way to do this is to cut to the person speaking everytime they speak. However, this creates quite an awkward feeling – and, as the audience, we start to become aware of the editing.

Why is this? Because by editing so that the speaker is always on camera we start to notice the editing for the obvious reason you are making a point of cutting to the speaker. However, if you cut to what is visually important no matter who is speaking, the editing hopefully becomes less visible and the scene feels more fluid.

Also, the person speaking isn’t always the most important person in the story. Because they say acting is reacting. Therefore, you will want to see how someone is reacting to those words being spoken to them.

Imagine a scenario where a police officer is informing our hero that his wife has just been killed in a car accident – do we want to see the officer while he’s speaking the whole time? Of course not – it’s far more important to see how the main character reacts to the news.

This is a very obvious example. However, there’s also more subtle reasons during a conversation you might not always want to be on the person speaking.

How about a close up of the speaker’s hands which shows how they are really feeling? Perhaps – in the wide shot – the speaker looks and sounds confident as they are making a speech on stage to a large audience. Cut to a revealing close up of the speaker’s hands fidgeting nervously…

Remember: an editor is a storyteller of equal importance to the writer and the director.

Tip 6: Follow the Eyes

This is an interesting one. I’m not sure if it’s really a basic editing tip but still worth including, I feel.

They say the eyes are the window to a person’s soul. In other words, our eyes give away more deeply hidden feelings in a powerful way. Humans are programmed to read each other’s expressions, especially the eyes.

So then it makes sense for us as editors to think about the eyes when we are cutting a film together. Legendary editor Walter Murch has an interesting technique.

“Our blinking is tied to what we’re thinking, and how we’re reacting to what’s around us. I try to hit the stop button just ahead of where they blink. So the frame before they blink. That’s a way I have of tuning my reactions to the unconscious reactions of this actor; to his character.” Walter Murch, editor and sound designer on Apocalypse Now, The Godfather I, II, and III, American Graffiti, The Conversation, and The English Patient.

He’s even written a book titled In The Blink of An Eye.

What I like about this idea is how Murch has found a way to connect himself to the story and the performances which form the central core of the story. Which leads nicely onto the next tip…

Tip 7: Immerse Yourself in your Edit

I’ve been a professional composer, writer, screenwriter and editor during my career. I find they all have a similar need to get “into the zone”. It’s simply not possible to truly dig deep enough into the project if you’re being distracted every few minutes.

To truly get the best results, I have to lose myself in what I’m creating. Everything around me fades into the distance as I go deeper into what I’m doing.

Because at some point you have to let go of the rules and technical stuff and just start feeling it. This is why practice is so important and also why getting familiar with your equipment is so important too.

As an example, for composing I used an Atari ST with software called Notator for over 10 years. It had 1 mb of RAM and no hard drive – song files had to be saved onto floppy discs. But, after years of working with one machine, I really knew how to use that thing. This meant there was less time spent learning how to use something, and more time “in the zone” getting lost in the music.

Maybe that’s a problem these days, with everything changing so rapidly. New machines, new software, new devices, new formats – and every time something changes we all have to spend time getting familiar again, so we can get on with the important stuff: being creative.

This is why when people are obsessing over grading technicalities and shooting log footage to get a better dynamic range in their images, I just want to say, “Dude, learn to do the basics first, so you can start feeling your movie.” Getting familiar with your kit should be like getting to know a great life-long friend. You should know the stuff so well you’re just doing the boring stuff instinctively, so you can immerse in the creativity.

Eager to learn more?

Join our weekly newsletter featuring inspiring stories, no-budget filmmaking tips and comprehensive equipment reviews to help you turn your film projects into reality!

Simon Horrocks

Simon Horrocks is a screenwriter & filmmaker. His debut feature THIRD CONTACT was shot on a consumer camcorder and premiered at the BFI IMAX in 2013. His shot-on-smartphones sci-fi series SILENT EYE featured on Amazon Prime. He now runs a popular Patreon page which offers online courses for beginners, customised tips and more: www.patreon.com/SilentEye