How To Write A Short Film: FREE Film School

The basis of any short film is the script. And in this article I’m going to tell you what I’ve learned about how to write a compelling short film, with the potential to win awards and impress investors.

The first short I ever wrote, with no knowledge of screenplay writing, was picked up by a TV company in the UK. But back then I was still raw. In the meantime, I’ve learned so much about screenwriting. Things that will save you time, help you create a perfect structure and add the necessary emotional layers to your screenplays.

Learn how to write a screenplay in 7 Steps.

- GENRE

- STORY IDEA

- STORY = CHARACTER

- STRUCTURE

- BUT & THEREFORE

- SUPPORTING CAST

- RESOLUTION

GENRE

One of the biggest differences between a professional screenwriter and an amatuer is an understanding of genre. Other tutorials on how to write a screenplay will give you a set of tips to follow, as if every genre requires the same – a setup, 3 dimensional characters and so on.

In fact a lot of screenwriting books do this too. They talk as if every movie has the same level of character development and the same kind of structure. But if you study movies, you’ll find each genre is written in a different way.

And one of the biggest failings of the new writer is lack of understanding of genre.

So what is genre?

The genre of a film is basically just the type of film it is. The big general genres like horror, thriller, romance, drama, comedy and action. But there are also sub genres.

A film noir is a sub-genre of the thriller genre. And a film like Blade Runner is a science fiction noir. So that means it has elements of science fiction but also contains many elements of those old film noirs, made in the 1940s and 50s. So the writers of the screenplay absolutely understood the noir genre, as well as science fiction.

Sub-genres

Horror films can also be divided into sub-genres. So is your script going to change depending on the genre and sub-genre. For example, a slasher horror film does not need complex, multilayered characters. But a mystery horror film, like Rosemary’s Baby for example, does.

When I first started writing I had no clue about genre. So I just wrote what I thought was an interesting story. The problem is, if you don’t know your genre, you can put a ton of time and effort into the wrong things.

Fans of slasher horror films probably don’t want to sit through an hour of slowly building tension, like in Rosemary’s Baby. After 10 minutes with no shocks or gore, they might just stop watching your movie.

But if you watch a dozen slasher horror movies before you start writing one, you’ll get a good idea of what is expected.

Exposition

Did you ever wonder why Christopher Nolan films have so much exposition in them?

Exposition is when characters in a film explain the plot for the benefit of the audience. It can come across as bad writing, if done in a way which feels unnatural. Screenwriting manuals will often tell you to avoid exposition as much as possible.

And yet one of the most successful filmmakers ever does it all the time.

Did you know Christopher Nolan is a fan of film noir? Did you also know one common element of film noir is characters explaining the plot?

So perhaps we can make a guess that Nolan’s love of film noir led him to see exposition as an attractive storytelling method.

Film noir

Film noirs used exposition because it was cheaper (and quicker) to have a character tell everyone what happened than to film it. In fact, the whole genre of noir came out of budget restrictions. Filmmakers had to think of innovative ways to tell their story, without so many sets, without 100s of extras and truck loads of equipment.

My point is, you can pretty much trace Nolan’s huge success back to his understanding of genre. Because film noir has informed all his movies since, reinterpreted in his unique way.

We can’t say what’s wrong or right about a story unless we first lay down the genre rules. Without those rules specific to each style of movie, how can we know what an audience expects?

Without referring to genre, we’re basically saying we don’t care what our audience wants. And that is a very egotistical way of creating a story. And one that is doomed to fail.

Why is genre so important?

Well, think of your own movie going experiences. If you go to see a comedy, you’re expecting to laugh. That is basically your number one demand from this movie. Multi-layered emotional character arcs and perfect story structure are secondary needs.

If you go to see a romance, you’re obviously expecting something romantic to happen in the story. You’re expecting the characters to act in a romantic way. You’re expecting the majority of the movie to be about the theme of love.

On the other hand, if you go to see an action movie, you don’t give a darn about the romantic element. You want to see epic action sequences acted out by tough characters.

If you go to see a drama, however, now you want those multidimensional characters with layered emotional character arcs.

And this is true of short films as much as it is of long form films.

STORY IDEA

Once you’ve chosen your genre, you can now think about your story idea. Of course, you may do this the other way round. You might think of a story idea and then consider which genre it fits into.

For example, you might have an idea involving a crime. Like a bank robbery. This might lend itself to the thriller genre. Or the film noir thriller sub-genre. That depends on how you want to tell it.

By combining your story idea with a genre, you define what is required in the screenplay. For example, is the film Drive an action movie, a romance, a thriller, or a film noir thriller? Probably a little bit of each.

The director, Nicolas Winding Refn, is really an arthouse director. Which is why he was able to make what is quite an unusual film. But on release, a number of viewers complained the film did not deliver what they were expecting. Because the film was sold as an action car chase movie, but turned out to be something a bit weirder than that.

How do we find ideas for stories?

The first thing to understand is that everything is a story. This video is a story. What you did today is a story. Why you are watching my video is a story.

But I get it. “How do I find that unique one in a million idea that everyone will think is awesome and make me a successful filmmaker?” I hear you ask.

That was the mistake I made when I started writing. I thought an idea had to be mind blowing or there was no point in telling it. But this way of thinking can result in rather artificial or gimmicky stories.

With experience I’ve learned that great stories are all around us. From our own life experience, from news articles, from stories friends tell us and so on. The challenge here is to turn those inspirations into a short script.

So what is the common element of all stories, no matter what genre?

STORY = CHARACTER

If you understand one thing, understand that character equals story.

The main character – sometimes known as the hero or protagonist – not only drives your story, but also forms it.

But what do I mean, character equals story?

Many guides on how to write a screenplay will tell you character is an element amongst other elements. But what I say is character is everything, not just an element.

Therefore, by forming the character, you are forming the screenplay.

Let’s take the example of the story Pinocchio. Pinocchio is the main character from the children’s novel The Adventures of Pinocchio written in 1883. Pinocchio is a wooden puppet who wants to be human. The problem is that he frequently tells lies. And when he does so, his nose grows longer.

Now, even if for some reason you’ve never encountered the story of Pinocchio, either from the book or the 1940s Disney film (or later versions), I’m sure your mind is conjuring up all kinds of scenarios to do with a puppet becoming human and lying and noses growing.

The adventures experienced by Pinocchio generally stem from a naive puppet wanting to become a human boy and his major flaw of lying. In other words, the character of Pinocchio forms the story called Pinocchio.

What happens when character doesn’t = story?

Let’s say you want to write a science fiction story about a new drug which makes people superhuman after taking it. So you start to get ideas for this drug and what it could do. You start to imagine scenes and start putting these scenes together.

At some point in this process, a main character forms. But only because you know a film has to have a main character. Problem is, you’re not too interested in this character. But you know he or she has to be there to experience these scenes you came up with.

Basically, you invent a main character to hang your series of scenes on. But they could be anyone really.

What happens is the main character in this script often feels like a victim of circumstance. Things out of their control are just happening to them for no apparent reason. It doesn’t feel like they’re driving the story. Rather, the story is driving them.

That’s because, in fact, the writer has made the drug the main character.

Now let’s go back to the start and try again

This time, you have an idea for a science fiction story about a new drug which makes people superhuman. But instead of writing a bunch of scenes around the drug, you stop and think about character.

What kind of character would be most attracted to this drug? Perhaps a guy who was bullied all his childhood and is still bullied now as an adult. By his boss, his wife, his so called friends.

Basically, he’s a wimp.

OK, this story is already sounding a little old fashioned, but it’s fine for this example. The point is, this is a guy who would do anything to get his hands on this drug. Perhaps.

So now we have a rough idea of our main character. Does this guy invent the drug? Or is he recruited as a willing guinea pig?

That’s up to you the storyteller to decide. What’s important is the character is consistent and that the character’s actions drive the story.

What does your hero want?

When we refer to the hero of a story, we really mean the main character or protagonist.

It’s often good for the hero to have an exterior need which somehow satisfies an interior need.

For example, our hero has to beat his boss in a charity boxing match. This will show everyone he’s not the wimp they all think he is. More specifically, to meet his inner need, he wants to show his bullying father. A man who has always been hypercritical of him.

But the boss is a fitness freak who works out at the gym twice a day. While our hero is all intellect and little muscle. But with the aid of this new drug he becomes a hulking superhero, easily capable of winning the match.

Do you see how using character brings depth and consistency to your story? But what about structure?

STRUCTURE

Oscar winning screenwriter William Goldman said “screenplays are structure”.

To include the full quote, “Screenplays are structure, and that’s all they are. The quality of writing – which is crucial in almost every other form of literature – is not what makes a screenplay work. Structure isn’t anything else but telling the story, starting as late as possible, starting each scene as late as possible.”

That’s a great tip. But for now, think in terms of beginning, middle and end.

So you have your genre, you have your idea, and you have a main character who somehow reflects or connects with that idea.

The next step is to think about what might happen for the duration of the story. Good structure is not only part of a good screenplay, it helps you write a screenplay. So you can think of your story as 3 phases:

Beginning

The beginning is the setup or introduction to the story. How you write this depends a lot on the genre of the screenplay. You might want to spend time establishing your main character. Or you might just want to get quickly to the main action.

How long this section is will depend on the whole length of your film. If you are making a 2 minute short, you probably don’t want a 90 second beginning.

Silent Eye is a series of 5 short films I created. You can watch them via Amazon Prime or Patreon.

Episode 1: You Have Been Chosen is about an indecisive woman who downloads an app which promises to make better decisions for her.

As the whole script needed to be about 10 pages, I gave myself 2 pages for this beginning phase. And in those 2 pages I showed how indecisive and unhappy the main character is. This motivates her to download the Decider app.

Middle

The middle of your script would normally form the biggest portion of the script as a whole. This phase is where the action develops and builds towards the end. This is where you can explore the ideas, the drama and the conflicts of the story.

We often start this phase when something new and unusual happens to the character.

In You Have Been Chosen the hero is sent an invitation to download the decider app. Her decision to download it changes the course of her life completely. And that’s the kind of event you would think about putting at the start of this section.

Now we follow her journey as she allows the app to make her life decisions. In this middle section, everything gets better and better for her, as she does everything the app says. Even when the app appears to be making bad decisions, the app is eventually proved right.

The middle section doesn’t just go in a straight line – it develops. The hero gets more entangled in the consequences of their action taken at the start of this phase.

I believe you will create a stronger script here if the stakes get higher and higher, the further the middle section progresses.

End

This is the climax of the story. The point at which everything that has gone before comes to a moment where a final confrontation can no longer be avoided. Like the beginning, this phase is usually somewhat shorter than the middle.

In You Have Been Chosen, the hero is instructed to do something she would never have contemplated doing at the start of the story. But the raising of the stakes during the middle section now leaves her with a fatal decision: lose everything the app has given her or commit a terrible deed. Which is it to be?

And in the screenplay for this short, this end section arrives at page 9 of a 10 page script.

Remember Genre

Now, this short is a science fiction thriller. So a dark, disturbing and murderous ending is appropriate.

But if your short is a romance, it’s more likely to be the lovers last chance to profess their undying love for each other. If it’s a drama, the climax will often relate to the hero’s inner demons. In an action movie, the hero will need to defeat whatever evil force is trying to take over the world.

If you know your genre well, you will have a better idea of how your short should progress during the beginning, middle and end. The originality of your work will come from the imaginative way you approach the genre and place your unique stamp on it.

How Long?

Part of your structure decision is deciding how long to make your short. Everyone works differently, but I personally recommend deciding how long your short will be in total before you start writing.

Make your short as short as you can.

I’m a festival director as well as filmmaker. And one of the most common reasons for a film to miss out on selection over another film is length.

Ask any other festival director and they will say the same. Filmmakers have made a good film, but they weren’t ruthless enough when writing or editing. A story beat that could have been told in a page or half a page is dragged out over several pages.

A common fatal mistake made by new writers is to start writing with no thought to the structure. Their scripts (and resulting short films) are often bloated and the pace drags. But by deciding on the total length of your script first, this will help you to keep your short tightly paced.

Story Beats

Once I’ve decided a length for my shorts, I write a story beat for each page of the script. A story beat is when something happens or changes. This means something is changing in the story roughly every minute and this helps to keep people watching.

Of course you can write a 30 minute short, consisting of 1 scene of dialogue between 2 characters, if you want. As long as you’re aware that you’ll have to work extra hard to keep your audience’s attention.

BUT & THEREFORE

Avoid your story going “this happens and then this happens and then this happens”. These kinds of stories are what’s known as episodic. In other words, there’s no twists. Something happens and then something else happens – just a series of events.

Instead, try to make each story beat a “but” or a “therefore”. Like this:

Bill is a nerdy wimp who turns down a challenge by his muscled boss to a charity boxing match. But Bill reads about a pill which gives you superpowers. Therefore Bill orders some of these pills and now accepts the challenge. But just before the match, Bill’s wife finds the pills and throws them down the toilet…

The plot thickens…

Do you see how using these 2 words helps you to give your story structure? The twists and turns of your story are the story beats you hang your whole screenplay on.

However, if you used the word “then” instead, you could write anything. Like this:

Bill is a nerdy wimp who turns down a challenge by his muscled boss to a charity boxing match. Then Bill goes out to lunch with his friend. Then Bill goes home and watches TV. And then Bill mows the lawn. And so on…

All these events are unrelated. They don’t drive the story, they don’t create any structure and they lead to an aimless wandering plot that people will soon get tired of watching.

SUPPORTING CAST

So I’ve talked a lot about the hero of the story and how their character is the story. Other characters in the story – the supporting characters – are just that: they support the hero character.

Now, I don’t mean they are kind and caring characters looking after the hero. Far from it. Although that might be one type of character.

What I mean is they support the depiction of the main character. In a sense, they are facets or reflections of the hero. They are there to represent ideas, emotions, personalities that conflict with or emphasise the idea of the story.

For example, that idea I just had about the wimp who takes a superhero pill to beat his muscle-bound bullying boss in a boxing match. The boss character is in some ways the direct opposite of the hero. He represents perhaps what the hero wishes he could be.

So, you see, the boss is not just a randomly generated supporting character. He is defined by the hero. And all your supporting characters should in some way derive from the hero too.

I say again…

And this is why I say the main character is the story. Because they define literally everything in the story – supporting characters, story beats, locations, props, dialogue – everything.

And once you understand this and apply it to your story, you’ll save yourself a huge amount of time. Then, all you need to do is create the main character and the rest grows from that. And it helps you stay on track.

Because one danger in screenwriting is to get lost in the development process. If something isn’t right, we make changes. But this has a domino effect on the rest of the script. And it’s very easy to lose track of what you originally wanted to do.

Metamorphosis

Your script can then mutate into something completely different. As a writer your mind gets tired and you can’t tell any more what is right or wrong. So you show it to some friends. But they all have different ideas of what you should do. And now you’re more confused than ever.

But by letting everything grow from my main character, I find I never get lost in this way when I’m writing. Because I simply refer back to the main character. As long as any changes I make are true to that character, then there’s a good chance they will be productive.

If you get your main character right, he or she is then the anchor which holds the rest in place.

RESOLUTION

How your short story resolves is up to you. Some shorts have a satisfying ending, where the hero learns and changes. This is especially true in dramas.

But take the short horror film Lights Out, which was such a huge hit on YouTube it was made into a feature film.

This short is the model of brevity. There’s almost no setup at all. And the film ends with a shock which doesn’t resolve anything. It rather leaves you in a state of suspense. We don’t know what happens to the hero at the end and so we can only imagine what might have happened.

And of course leaving the audience in suspense like that is much more disturbing than having a final battle or some kind of resolution. Even having the hero killed at the end would probably be less disturbing than leaving us wondering.

So, again, how you resolve your story depends a lot on the genre of the film. But also it’s a creative choice. Do you want to leave the story open ended or do you want the story to end in a more comforting way?

Or maybe it just suddenly stops without warning.

FREE Film School: Week Six Task

So far we’ve been practicing thinking about film differently. We’ve also had a go at telling stories visually. Last week we looked at our own experiences for a source of inspiration.

The task was to write 1000 words on a period of your life. How did that go?

If you managed to write out 1000 words (or more), then you will have some stories fresh in your mind. You will also have a deeper thought process going on about them than before. Can you see them as films?

This week’s task is to write a 10 page screenplay using inspiration from those 1000+ words. You can make it biographical or let your fiction be inspired by a true story. Or you can cover the general themes and beats, but fictionalise it completely.

You might need some screenwriting software. Rawscripts is a free online screenplay formatting program.

Personal stories

Any personal story can be adapted to any genre. Take your own experiences and transpose them to a space opera. Or let your horror be inspired by themes close to you.

My weird sci-fi feature was also inspired by events in my life, some past some present. The line between reality and fiction blurred. I found myself directing actors playing characters based on real people, in the locations where the real events took place.

You don’t need to go that far. And you don’t need to try to include everything from those 1000 words. In fact, please don’t.

It might only be 3 words from those 1000 words which now form the inspiration for this short. Writing them was in part to connect filmmaking to emotional stories. But also as an exercise to get ideas flowing.

Read more: Writing a Screenplay – 2 Things You Must Do

Read more: Writing a Screenplay – First Steps

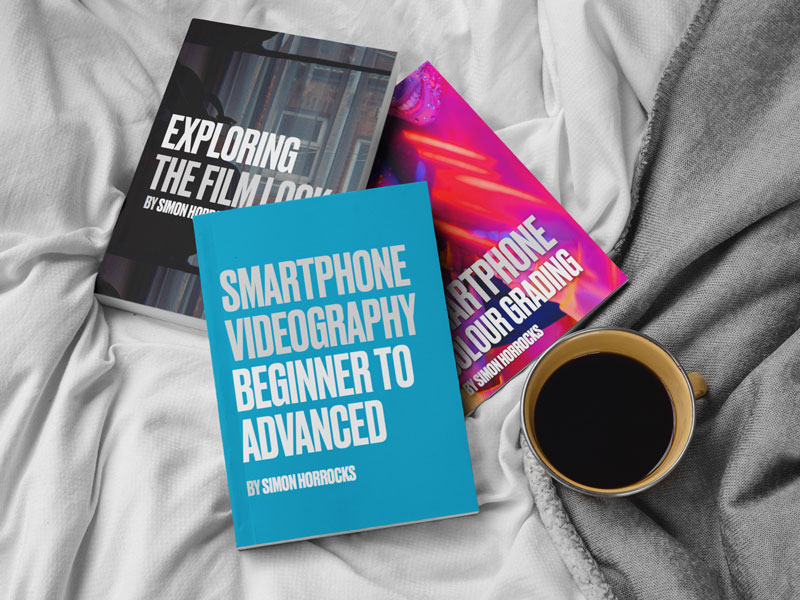

Smartphone Video – Beginner to Advanced

If you want to know more about smartphone filmmaking, my book Smartphone Videography – Beginners to Advanced is now available to download for members on Patreon. The book is 170 pages long and covers essential smartphone filmmaking topics:

Things like how to get the perfect exposure, when to use manual control, which codecs to use, HDR, how to use frame rates, lenses, shot types, stabilisation and much more. There’s also my Exploring the Film Look Guide as well as Smartphone Colour Grading.

Members can also access all 5 episodes of our smartphone shot Silent Eye series, with accompanying screenplays and making of podcasts. There’s other materials too and I will be adding more in the future.

If you want to join me there, follow this link.

Simon Horrocks

Simon Horrocks is a screenwriter & filmmaker. His debut feature THIRD CONTACT was shot on a consumer camcorder and premiered at the BFI IMAX in 2013. His shot-on-smartphones sci-fi series SILENT EYE featured on Amazon Prime. He now runs a popular Patreon page which offers online courses for beginners, customised tips and more: www.patreon.com/SilentEye