Actor Joshua Leonard talked to Filmmaker Magazine about how freeing it was co-starring in Steven Soderbergh’s iPhone shot thriller Unsane.

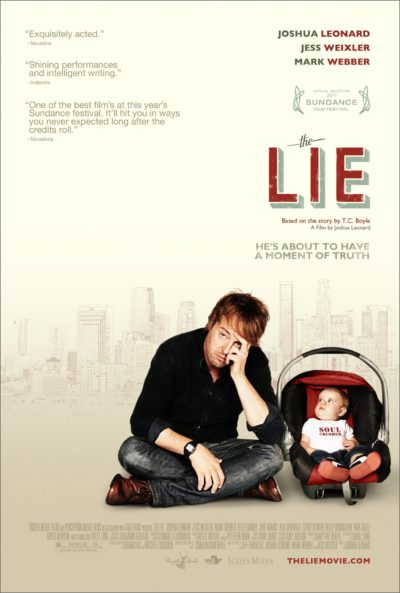

Joshua Leonard was first noticed in lo-fi sensation The Blair Witch Project. He went on to receive rave reviews for his performance in Lynn Shelton’s Humpday. As director, his narrative feature debut The Lie premiered at Sundance in 2011. Meanwhile, he just wrapped production on his sophomore feature Behold My Heart which stars Marisa Tomei.

Here’s an extract of what he said to Filmmaker Magazine, about getting work as an actor, improvisation, iPhone filmmaking and working with Steven Soderbergh.

Q: You land a role, you get the script, and what’s the first thing you do?

Joshua: I think the very first thing that I do when I get a script, that is something I’ve been chasing after, is start figuring out how I’m actually going to do the role. As opposed to trying to convince people that I am capable of doing the role. Other actors might disagree with me, but I always feel like when you go to audition for something, you’re kind of looking for the ocean in the raindrop.

When somebody just does a couple of scenes, you also want to know that there’s the breadth to also do the other aspects of the character. Whereas when you’re actually doing the movie, you can be much more specific to the moment itself. Because you have the entire structure of the screenplay to play off of. And you can really hone in on what the emotional truth is at that given moment in a character’s journey.

But I do think there’s a bit of a different thing when it comes to auditioning. Where you want to show that you understand the other aspects of the character, as well. So, I think when the job is mine, I just start reading the script a bunch. And looking at how the macro-arc that the character is going on is really broken down into bite-sized pieces and moments.

Because you never want to telegraph a resolution when you’re in the middle of the hardship part of the journey.

Q: And what’s your relationship to the text? Do you start memorising?

Joshua: I’m terrible. I’m awful. My process is – I read the script a bunch of times, I make some notes. If the role requires research for specificity of a life situation that I’m unfamiliar with, I try to do some of that stuff. I don’t focus on memorisation too much. I find if I imprint it in my brain enough times, and then say it’s 3/4 of the way there, and then get that last quarter – of the actual rhythm of it and all the specifics of the script – on the day, with the actors when I’m doing it, that it keeps it a little fresh.

Which might just be my way of explaining away laziness on my part! But it seems to work. I should also say I don’t do a lot of theatre and I’ve never worked with David Mamet, so… I haven’t done those shows where you really need to be word perfect. And I think my technique would probably leave me flat on my face, here – if I did have to do that.

For better off or worse, I think one of the reasons I get hired is – for a loose sense of naturalism. I have found the writers and directors I’ve worked with to be incredible collaborative. If there’s a word off here or a word off there. The most important thing being that we’re getting to the heart of the truth of the moment.

There might be a whole collection of directors or writer-directors out there, who are secretly resentful at me for not being word-perfect on their scripts [laughs]. But it seems to have worked thus far. Having participated in a number of projects that are tightly structured but completely improvised, from the dialogue standpoint. Where we know the architectural purpose of the scene but we don’t know how we’re going to get there until the day.

Q: Did you ever work with someone who wasn’t improvising on your level?

Joshua: I’ve worked with people who are master improvisers and I don’t think of myself as a master improviser. If the role is right, and I can wrap my mind around it, I can get pretty close. I always credit – for example on Humpday – I credit Nat Sanders, who edited that film as – along with Lynn Shelton… when you’re doing a film like that, you’re really relying on a good editor to take the exciting spontaneity that comes along with that type of process [to] hone that in so it’s not all over the place.

Because I think there’s a thousand terrible of every improv film that I’ve ever done. And certainly someone who wasn’t an adept storyteller in the editing room could have made a bunch of bad movies out of the things that we said. So I think being a good improviser also relies heavily on working with a team that’s going to take that and hone it in the editing room.

That said, I have worked with actors who just don’t like improvising. And my wife Alison Pill is one of them. She likes a script. She does not like to improvise. She really is a “text is God” kinda person. And I respect that. And I think she’s got a specific skill-set that I’ll probably never have.

I mean, what I do in that looseness, it doesn’t apply to Mamet, it doesn’t apply to Chekhov, it doesn’t apply to Shakespeare. I might fail miserably trying to do those things. So I think part of it just comes along with the fact – because Blair Witch was my entre into what later became my career – I really kind of came in sideways, in a way that happened to work for me [and] play to a strong suit.

I don’t think being a good improv-er is a sign of a good actor, it’s just one tool in the toolbox; one colour in the palette.

Joshua talks some more about improv acting – how an improvised scene might be 30 minutes long, then the editor might cut it to a more efficient 5 minutes; the difference between dialogue in imrpov and scripted; also how Mike Lee works with actors to write his scripts.

Q: What do you need from a director as an actor?

Joshua: One of the things that’s really changed for me as an actor, since starting to direct – I’ve stopped laying so much weight on the shoulders of how something feels inside me, when I perform it. I think I would approach a scene and think, “I’m gonna know when I got the right take.” Because it’s going to feel like I got the right take. It’s going to feel like it was all honest. And I would keep asking for takes.

And then as a director, especially with a film like The Lie, where I directed myself, which meant I was then in the editing room, editing myself, realising that a lot of those times when I’m looking for something perfect, that feels perfect inside – it’s not the way it’s reading on camera.

I would find 2 things. One is: sometimes it was just way better when it wasn’t as clean. People always talk about the Leonard Cohen, “there’s a crack in everything and that’s how the light gets through.” The imperfections making something that much more potent. And so this striving toward a perfect take is an actor is actually sometimes sterilising, in a way that it sometimes less interesting.

And then the other thing that you sometimes find is, those 3 takes that felt so different to me, they look basically the same when you watch them back. [laughs] So I have become hopefully way less of a pain in the ass to directors that I work with, if they say they got what they needed.

The other thing that I’ll say is, one thing I’ve found is a crucial tool to me as an actor, is know that you can’t come up with a list of demands for your director. Because you’re going to get all different kinds of directors. And some directors are amazing with actors, and really want to get in to the touchy feely. And some directors – it’s just not their bag. They’re more technical people.

And then occasionally you get a director who is great at all of it and approaches it holistically. And that’s fantastic. But you never know what you’re going to get. And I will also say that some of those directors who aren’t great at talking to actors sometimes make great fucking films, with great fucking performances. [laughs]

So I think it’s out job as actors to do enough work that we show up and can do our job even if we are not getting what we think we need.

Q: I imagine it was very freeing acting in front of an iPhone.

Q: I imagine it was very freeing acting in front of an iPhone.

Joshua: Making Unsane was one of those experiments that I would have been way more scared about if Steven Soderbergh wasn’t the guy holding the iPhone. [laughs] Because, at the end of the day, if it works or if it falls on its face, it’s kind of his to win or lose. And honestly, I don’t know for sure, but I don’t know that he gives a fuck.

I think part of what was so enticing about this project – and let me just step back and I say, I’m not playing cool – of course when Steven Soderbergh called me and said he wanted to do a film with me I said, “Yes”. And it didn’t fucking matter what it was. [laughs] But what Steven said in our very first conversation was, “if the iPhone technology existed…” – we shot this film on the iPhone 7, which shot 4k native – “…if this technology existed when I was 15 years old, it’s all I would be doing with my time. That’s what I want to do. I want to make a film with nobody. I want to make it fast.”

This notion of how exciting it is when you can reduce the time between impulse and execution. And how much amazing stuff can exist in that place. That so often you don’t get to have on a film. There’s not a ton of spontaneity on a film set that’s got a crew of a 150+ people and takes 2 hours to set up a shot, because you have to move the lights around the room.

I think nobody is working at their spontaneous best at that point. That said – we’re not going to go and make Dunkirk on an iPhone. [laughs] It works for a specific type of project and I think this was a film that lended itself to going fast. And really trying to ride initial impulses right into the scenes themselves.

The iPhone is such an omnipresent piece of technology in all of our lives at this point, that it completely removes any sense of elevation. You’re no longer making film with a capital F, when you’ve got an iPhone in your face. I think there’s something so fucking freeing about that. From a psychological standpoint, it takes up much less space in a room. So it’s no longer… Susan Sontag used to say… like the camera being the barrel of a gun.

And I think even on a subconscious plane, when you’ve got one of these big cameras with a big lens, and it’s pointed at you in the scene… I mean, maybe Daniel Day Lewis can ignore it and not see it. You try to push the awareness back in your mind. But there’s always an awareness, because you’ve got this huge piece of machinery and you know it’s sole purpose is to record your every tick.

And with the iPhone, it’s just this little tiny thing that you see in your life all the time. So it removes the self consciousness. You’re just kind of able to be in a room, and be with the other actors. and this film – especially in some of the more intimate scenes, when we would go in a room to shoot a scene – it would be: 1 guy recording sound, Steven holding an iPhone and a lot of the time it was just the 2 actors. So, those padded room scenes between Clare and I, there’s 4 people in that room.

As opposed to 20 people, in many situations on a bigger film. So you’re just so much lighter on your feet. Not that the iPhone is without its own aesthetic, to some extent. But I also think we’re doing a lot of talking about the iPhone with this movie because it’s still pretty novel. I mean, Sean Baker did it with Tangerine. And I think that was a film that stood on it’s own without the iPhone. But there was certainly a lot of discussion around it.

That said, hopefully if we’ve done our jobs right, after the first 2 minutes of the film, I don’t think anybody’s going to be thinking, “Oh this was shot on an iPhone.” Which is a big difference – technologically speaking – to when we made Blair Witch. When we had to have the conceit students are making this film with cheap equipment and that’s why it’s going to look like shit.

Whereas with this one, I don’t think – if nobody told you that this film was shot on an iPhone – I don’t think anybody would know.

Steven’s fascinating to work with. I loved working with him as an actor. He’s very respectful of actors. He’s not a micro-manager at all. That said, he’s one of the least indulgent filmmakers I have ever worked with. Maybe the least indulgent filmmaker I have have ever worked with. In the sense that, he is so clear about what he needs.

You’ll look at a scene, you’ll look at a page long monologue that you have, and he’ll come to you and give you the information which is: “I’m going to set the camera up in this corner and I’m going to use this angle for these 3 sentences. At which point I’m going to cut down to this angle. And I’m going to use that from this word until this comma.”

That said, he’ll also say, “If you want to start earlier and ramp into it… If you want to go later… whatever helps you in your process, you are welcome to do.” Because he’s already edited the film in his mind and as soon as he leaves set he gets on his laptop and puts it together.

The night of the wrap party for Unsane, we all went bowling. And Steven sat at the bowling alley on his laptop. And then he came over to Clare and I, as the party was winding up, and said, “If you want to come back to my room, I have a cut of the entire film for you to watch.”

As soon as the wrap party was over, and we had been shooting all that day, we went back to Steven’s room and watched the film from start to finish.

You can listen to the full Filmmaker interview below:

Eager to learn more?

Join our weekly newsletter featuring inspiring stories, no-budget filmmaking tips and comprehensive equipment reviews to help you turn your film projects into reality!

Simon Horrocks

Simon Horrocks is a screenwriter & filmmaker. His debut feature THIRD CONTACT was shot on a consumer camcorder and premiered at the BFI IMAX in 2013. His shot-on-smartphones sci-fi series SILENT EYE featured on Amazon Prime. He now runs a popular Patreon page which offers online courses for beginners, customised tips and more: www.patreon.com/SilentEye

Q: I imagine it was very freeing acting in front of an iPhone.

Q: I imagine it was very freeing acting in front of an iPhone.