The History of the Long Take: FREE Film School

Just over a week from now, we will start filming the 5th episode of our smartphone-shot scifi series, Silent Eye. For the previous 3 episodes, I decided to shoot in quite a “choppy” style. My hunch was that a more instinctive movement of the camera would play to the strengths of the smartphone.

You might compare this style to “Cinéma Vérité”, although that method often included long takes. The result I was looking for was something urgent, chaotic and fluid. A kind of organised chaos.

Because while most low-budget digital shooters (including DSLR and mirrorless) are trying to make their films look like they were shot with more expensive cameras, I felt that was a false goal. I’m a big fan of 80s and 90s low budget films that looked rough but carried charm (eg Clerks and Slacker). So I wanted to embrace a kind of scruffy shooting.

However, for Episode 5: Sleep House we have decided to shoot in a more classical style. We will use longer takes, less camera movement and aim to create something more polished, less chaotic. While it suits the rather solemn theme of the story, it also suits the episode’s director (David Thackeray) who has previously directed theatre.

Using long, mostly still shots, mostly interior is in some ways similar to how we see theatre. The actors move around the frame and the set (location), while the camera watches more passively. And a passive watcher is more like a member of the audience in a theatre. When you go to see a theatre play, your point of view is fixed (unless you change seats).

So, all that backstory leads us to the point of today’s post – the long take; should we use it, what effect does it have and why?

What is a Long Take?

How do we even define a long take? It’s a bit like asking “how long is a piece of string” isn’t it? Let’s look at some stats.

Stephen Follows does fantastic statistical work for cinema. He’s something of an acquaintance of mine as we met a few times some years ago. He helped me package my feature Third Contact. And we discussed a parkour project he was looking at producing (I came up with some narrative ideas).

As I Googled to find out the average shot length, I had a feeling Stephen would have written something. And lo and behold, there it was.

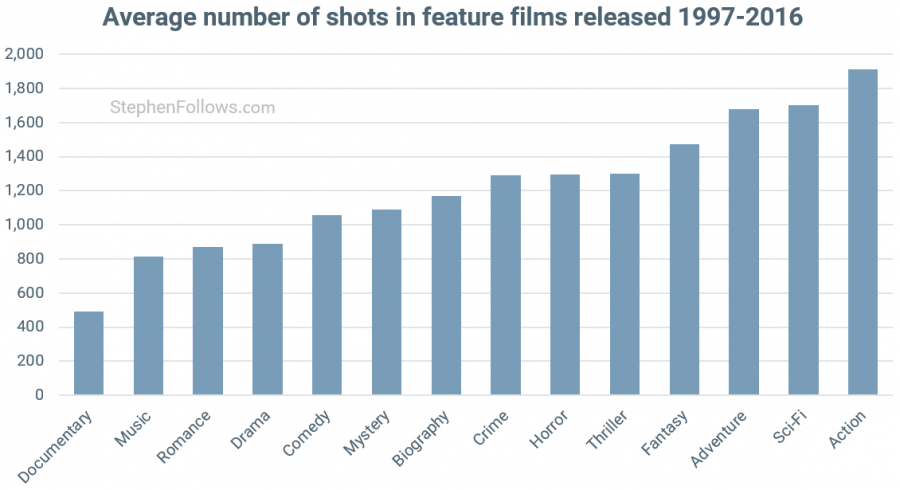

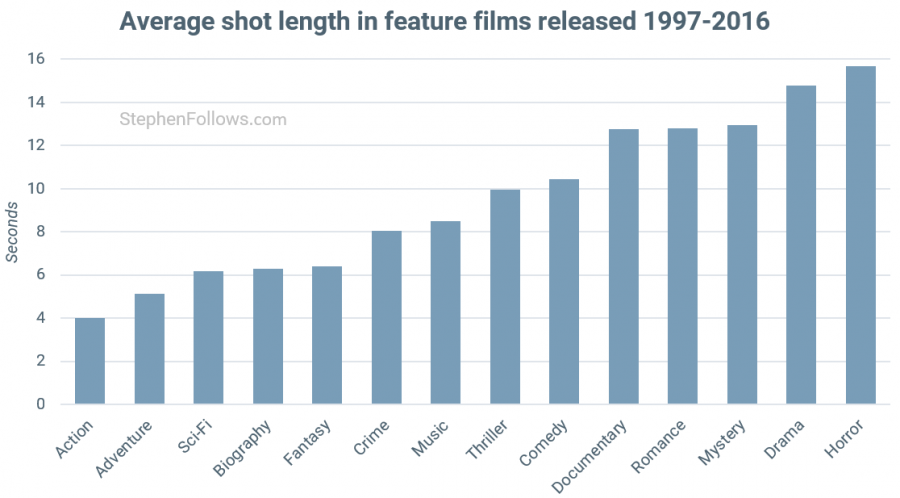

So Stephen has crunched the numbers and come up with the following (ooh a pun):

And…

So then, quite revealing, isn’t it? He also looks a little into how average shot length has decreased over time, especially for action movies. In other words, there’s a trend towards shorter shots and faster cuts.

So, as expected, fast paced genres such as action, adventure and sci-fi have the shortest shots. While films that draw you in slowly – mystery, drama and horror – have the longest. Also, note documentary and romance are equal in pace to mystery, which makes sense.

In a romance, we want our audience to be “seduced” like the lovers in the film, so quick cuts are going to ruin the mood. Imagine being seduced by someone who talks very quickly an abruptly. Ain’t gonna work… at least for most of us.

Also, in a documentary we expect to see long takes of people being interviewed or events happening in “real time”. Another reason why we might have longer takes in documentaries: often there’s only one camera. So there’s less opportunity to cut to another angle.

How long is a piece of string, again?

Well, in horror the average time between cuts is about 15 seconds. So for a take to stand out as long in a horror film it would have to be longer than 15 seconds. Action films have an average shot length of 4 seconds. So you’d only have to have say a 10 second shot for the audience to start to feel the movie is really dragging.

As predicted, there is no scientific definition of a long take. However, it’s certainly insightful to look at how the length of takes effects the style of the film.

The Long Take in Cinema

Back in 1948, Alfred Hitchcock attempted to make an entire 80 minute film in one long take. Except that in those days, a film camera could only hold a reel of film which lasted 10 minutes. To overcome this obstacle, Hitchcock tried to hide the cuts by moving in on a back of a character until the screen goes black, then pulling out again at the start of the next reel.

If you watch it now, the cuts are pretty obvious. But in the more recent Birdman, they again created a sense of a “1 take movie” by hiding the cuts. This time, however, it’s much less noticeable. The filmmakers mostly hid the cuts by cutting on a pan. This is more effective as the motion blur created by the pan makes the cut much less visible.

In the 1960s, Artist Andy Warhol collaborated with avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas to shoot the 485 minute long Empire (1964). They used an Auricon camera which allowed rolls of up to 33 minutes each. But since the invention of digital cameras, it has become possible to shoot continuously for much longer. Essentially, until the hard drive collecting the files is filled up.

Since then, films such as Timecode (2000), Russian Ark (2002) and Victoria (2015) have been filmed in one single take. These movies take the long take to the extreme. However, a long take is normally a lot shorter than 90 minutes.

So what other films can we look to for inspiration and insight into the effective use of the long take?

Filmmakers Who Use Long Takes

One of the most famous directors who had a tendency to use very long takes was the legendary Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. You can see this in his films, such as Solaris, Stalker and The Sacrifice. More recently, Paul Thomas Anderson has been known for long takes, often using a Steadicam. Check out Boogie Nights, for example.

Another famous example of a long take is the opening shot of Touch of Evil, by Orson Welles. This shot was so inspiring to later filmmakers, that many went to great lengths to include a long take in their movies.

Directors like Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese later employed this moving long take, what we might call a following shot. And this is a shot that is a lot easier for the low budget filmmaker to create now, with a camera and a relatively cheap gimbal.

But not all long takes are following, Steadicam-type shots. Look at the work of Stanley Kubrick for examples of long, motionless takes. For example, in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey the pace of the film defies almost all later sci-fi movies by being slow and drawn out. His historical drama Barry Lyndon also employs a pace that matches the formal tempo of the time, and the story.

Do Long Takes Make Your Film Boring?

Certainly, many watchers will struggle with the deliberately drawn-out nature of the scenes in Barry Lyndon. However, when I first watched it, I found that after a few minutes I settled in to the tempo. I understood the slow pace was part of Kubrick’s intended experience, so I accepted it. And then it becomes enjoyable and creates a strange, almost surreal formality. And in fact, the movie appears to be partly about this surreal formality of a bygone age, culminating in a duel scene which I found electrifying due to – not despite – it’s deliberate slow pace.

A scene where two men try to kill each other, with a referee and the clearly defined rules of combat, as devised by the “civilised” European aristocracy of the 18th century. Compare that to the frenetic, fast cutting brutality of the battles in an historical film like Gladiator, by Ridley Scott.

This Week’s FREE film School Exercise

So, if you’ve been following along with previous FREE Film School posts, you might be developing a story idea for the screen. We’ve looked at screenplays, storyboards and shot lists amongst other things.

We now know, shot length affects the pace of the film and tends to be shorter for action and longer for horror. So, how does that change the vision for your film? Do you see your storyboard differently now? Will you go with the convention of your chosen genre, or defy it?

How do we learn the power of the long take in cinema? Well, by watching it and then trying it ourselves. That’s the most straightforward and simple answer. Watch and observe how other filmmakers have employed it, then mull over whether this suits you and your style of filmmaking. If possible, give it a try yourself.

Long shots can create a more real, immersive experience. That’s because cutting from one angle to another is in some ways artificial. As humans, we do no suddenly change our point of view when we’re observing the world.

On the other hand, a long shot can lose an audience’s attention. While shorter shots with constant edits can help keep the audience attentive. It’s like sipping a glass of wine to some relaxing music, compared to playing a FPS video game after drinking a double espresso…

Eager to learn more?

Join our weekly newsletter featuring inspiring stories, no-budget filmmaking tips and comprehensive equipment reviews to help you turn your film projects into reality!

Simon Horrocks

Simon Horrocks is a screenwriter & filmmaker. His debut feature THIRD CONTACT was shot on a consumer camcorder and premiered at the BFI IMAX in 2013. His shot-on-smartphones sci-fi series SILENT EYE featured on Amazon Prime. He now runs a popular Patreon page which offers online courses for beginners, customised tips and more: www.patreon.com/SilentEye