Filmmaking: How Streaming Video Changes Everything

In the media world, getting an audience’s attention is the unspoken need of any creator who works with it. People in the media world don’t talk about it publicly, but it’s what everyone is thinking and worrying about daily.

Nobody goes onto a chat show and opens with “Thanks for letting me on the show, I really need as many people as possible to know about my new movie.” But we all know that’s why they’re there.

Brian Epstein was well-known for breaking the Beatles. He heard about the band through various avenues, a magazine, posters, a customer who walked into his record shopped and asked for their debut record, Bonnie and so on.

In other words, Epstein didn’t just happen by chance upon the most famous band ever. They had already done a considerable amount for themselves which led to someone like Epstein hearing about them.

After sowing up contracts with the Fab Four, Epstein set about signing them to a record label. After being rejected by every other label, they were eventually signed for Parlophone (part of EMI) with the contract awarding them 1 penny for every record sold.

Epstein had no previous experience managing bands and Parlophone very little experience with rock or pop acts. Regardless, this arrangement allowed the band to go from playing live to a few hundred kids to becoming a worldwide phenomenon.

A technology revolution

Why the Beatles became the band that changed everything is a subject that’s been covered many many times since. But essentially, one big factor was being the right band, in the right place, at the right time. It was a technology revolution that changed everything.

Essentially, new levels of mass production after the war using cheap but durable plastics meant most households could afford a radio. And most households could afford a record player and some records to play on it.

Added to that, TV sets were becoming available to more and more people. This meant, it didn’t only matter what you sounded like. From now on, what you looked like was also a huge factor in your success in reaching the masses.

Cut To: the Internet

Digital media had a similar effect on the media industry, but was more of an evolution than a revolution. Until, that is, the internet took over. The internet led to file sharing, streaming and the total domination of social media as a means of promotion.

So while the Beatles had radio, 45s and TV sets, whoever is famous now (I have no idea) has Snapchat, Tik Tok and the rest. There’s probably some trendy ones that I’m too old to know about, as well.

Who is desperate for a bigger audience right now (without ever mentioning it)?

Well…

- me

- filmmakers

- bands

- singers

- actors

- novelists

- bloggers

- vloggers

- YouTubers

- Instagrammers

- Influencers

- musicians

- journalists

- broadcasters

- painters

- performance artists

- theater writers, producers and directors (theatermakers?)

- app designers

- advertisers

- politicians

- companies with products to sell

- website designers

- film festivals

The list goes on, doesn’t it…

That’s a lot of people

Yes. The world is becoming more and more dependent on digital communication. Not only do we communicate with each other via the digital waves, but our inventions communicate with each other too.

What the heck has this to do with filmmaking, Simon?! Well, you know I like to take my time before I get to my point. And my point is that, as filmmakers, many of us seem to be living in the pre-digital age still.

Some very well-known filmmakers still insist films should be shot on film and be made to be shown in cinemas. And when it’s legends such as Christopher Nolan and Quentin Tarantino, a lot of aspiring filmmakers sit up and listen. Good work if you can get it, I say.

But be aware, in my humble opinion, films shot on film are not (and cannot be) the future. Aaaand… here’s why.

Pirates Ahoy!

When platforms like Napster allowed ordinary people to share music with each other, the music industry’s business model was undoubtedly destroyed. A physical thing has a value because there’s always some production cost involved and a profit to be made from owning the means of production (go Capitalism!).

But a digital thing which can be copied and shared in seconds has almost zero value. At least, using the old business model of selling things like songs pressed to vinyl and words printed on paper.

The music industry took to the courts and won the battle. But ultimately lost the war. People were not going to stop sharing digital copies of other people’s music. And unfortunately, time was not going to go into reverse to save the music biz.

Music streaming is now the primary medium through which people consume music. By making streaming convenient, the music industry saved itself from complete annihilation. The financial rewards, while far less, are better than nothing at all.

Netflix and the rest

There’s less money in music, but writing and recording a professional song can be done relatively cheaply these days. In contrast, making a film still costs about the same (if not more).

For example, Netflix gave Martin Scorsese over $140 million to make The Irishman. A film that is essentially a “made for TV movie” for the VOD age. When we used to talk about “made for TV movies” in the 1980s or 90s it was almost a disparaging remark. And they certainly didn’t get $140 mil thrown at them.

Netflix give huge budgets to names like Scorsese to make films, full of old acting legends such as Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. Well, it makes some sense to Netflix because these big, high profile titles drive subscribers. They also know this title will have longevity, so it’ll be paying them back over the next 20-50 years.

In a Streaming World, Audience Retention is your Boss

The mass production of radios and TV sets led to Beatlemania. But what changes will streaming bring to the business of making film?

The streaming business model is driven not just by acquiring an audience, but also keeping them. That thing I talked about previously: audience retention.

Why? Because digital content leads to file sharing, and file sharing means there’s no value in the work itself. Instead, the value is in the company which streams the work and its task is to stream works as conveniently as possible for the audience. By doing so you retain that audience’s attention (and loyalty).

Why is audience retention so important? Well, because online content is free. And for this reason streaming platforms’ business model is subscriptions.

Nobody had to subscribe to Parlophone Records to get convenient access to Beatles songs. Nobody had to subscribe to Odeon Cinemas to watch a Scorsese movie. But now, for the sake of their convenience only, they must subscribe to a streaming service.

But what happens when you subscribe to Parlophone Records to hear Beatles songs and the Beatles stop writing songs? Or when they simply can’t keep up with the demand to produce more songs and so risk losing the audience’s attention?

Do you see the difference?

In 1962, Parlophone could release Please Please Me by the Beatles, sell millions of copies and fill their bank account with enough money to keep them afloat while they wait for John and Paul to write some more hits. In 2019, the digital copy of Please Please Me is virtually worthless and streaming it doesn’t bring in enough cash to even pay your staff.

The bottom line is this: streaming is about subscriptions and subscribers demand regular content.

But how do you produce regular content and maintain the high quality level, which in the film business costs so much in time and money?

Amazon Prime: Charge per Episode vs Free for Prime Members

I’m currently struggling with this myself, working on my homemade Sci-Fi series Silent Eye. We’ve managed to produce 4 episodes in 2 years. I placed it on Amazon Prime but, at first, not free to view for Prime members.

I’d hoped to create maybe 8-10 episodes before making it available for Prime members. But as I found each episode taking so long to finish, I realised at the rate we were going this wouldn’t happen for another few years. So I decided to make the series open to prime subscribers with only 4 episodes online.

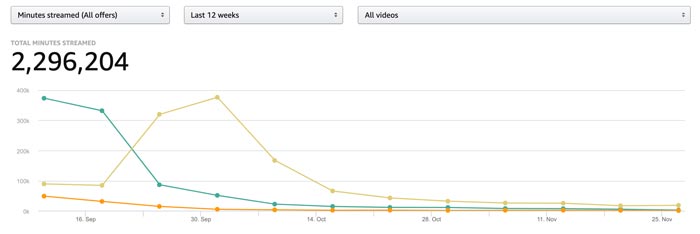

My hope and prediction was we’d get a lot more views. In fact this came true and viewers suddenly flooded in. But this traffic lasted a couple of months before dropping off again.

With Episode 5 nearing completion, it remains to be seen if adding a new episode will have any effect on the viewing numbers. But here’s what the slow content production model looks like:

The figures go further back than that, with a big spike in UK viewers (blue), but Amazon only lets me select up to 12 weeks (the orange line is Germany, the yellow line USA).

In terms of minutes viewed since we made it available to Prime members, we’re looking at over 5 million. Divide that by 15 minutes per episode and it equates to about 300,000 episode views.

But when viewers had to pay $0.99 per episode it was far far less than that. At most, 100 episodes for the first month of release, then down to about 5-10 episodes per month.

Now, if we were still pre-file-sharing days, and each of those 300,000 viewers had to pay $0.99, then you can see we’d have enough money in the bank to make many more episodes, expanding our team to make the process faster.

But with the subscription/streaming model, Amazon pays us a tiny fraction of that. We took about $2000 from those peak viewing figures (for 2 years work).

Compare to the ‘Constant Content’ model

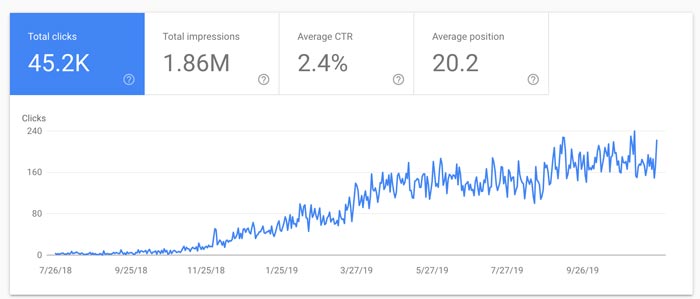

Since September 2018, I’ve been writing about 6 blog posts a week. This means I’ve been producing constant content. While each Silent Eye episode has taken 6 months to create from writing to final edit, a blog post takes me anything from 30 minutes to 5 hours (ost take me about 1-2 hours).

After about 14 months of that, this is the effect on our website traffic (USA):

Instead of a spike, we get a slow but constant increase in traffic. In other words, we’re not only retaining our audience’s attention, we are increasing our audience too. This constant content method allows us to build a momentum, while the old ‘intermittent content’ method has the momentum of a single explosion.

At best it’s boom and then bust. And the majority of people self-publishing online don’t even get the boom part.

This is all from my point of view as a single creator. Of course, Amazon and Netflix have thousands of creators producing content for them, so presumably their graph is a steady upwards climb too. But the question is, what does this mean for individual creators like us?

Before the internet changed everything, a boom effect was what filmmakers hoped for. That boom would project you into the public’s consciousness and you could live off that for a while.

But with content saturation, the boom is no good any more. It quickly fizzles out and you’re forgotten. Even if you make a brilliant movie, the money returned from that boom is now less likely to be enough to sustain your business as a creator.

Unless…

Unless as filmmakers we start to think differently. Survival has always been about successfully adapting to new circumstances. One of the advantages of the constant content model is we’re now able to build and maintain a connection to our own audience. While the Beatles had to rely on Brian Epstein and Parlophone Records to reach the masses, we don’t.

YouTubers who use Patreon to fund their filmmaking are effectively mini Netflixes. And as long as they continue to produce continuous content, their subscribers will continue to stay tuned and help fund their career.

Successful YouTubers have developed ways to produce constant content in a way that compensates them for the effort put in. They aren’t getting $140 million per 3.5 hours of content like Scorsese, but they aren’t shooting films which require the same time and effort. They’re also building their own audience.

Well known actor Mads Mikkelsen was recently in a movie called Arctic (2018) directed by Joe Penna. Now, it turns out that Penna is a musician who started a YouTube channel in 2006. Since then, by producing constant content his channel has acquired 2.7 million subscribers and over 400 million views.

After just over 10 years of this process, Penna got to direct a $2m feature film starring Mads Mikkelsen. I don’t know the full story behind how that film got financed, but I’m sure having 2.7m subscribers helped persuade investors. A steady build, it seems, can eventually lead to funding your dream project.

Eager to learn more?

Join our weekly newsletter featuring inspiring stories, no-budget filmmaking tips and comprehensive equipment reviews to help you turn your film projects into reality!

Simon Horrocks

Simon Horrocks is a screenwriter & filmmaker. His debut feature THIRD CONTACT was shot on a consumer camcorder and premiered at the BFI IMAX in 2013. His shot-on-smartphones sci-fi series SILENT EYE featured on Amazon Prime. He now runs a popular Patreon page which offers online courses for beginners, customised tips and more: www.patreon.com/SilentEye

So you made ~$2000 from your web series so far on Prime, which is not enough to continue producing it, IMHO. Free streaming is not paying enough.