Marketing Your Film & The Invention of Cinema

How was cinema invented and why is it still relevant today? This morning, I woke up and started going through the usual rubbish on Facebook on my phone. Then I saw an article shared by someone and that article was about a guy named Adolph.

No, not that Adolph. This one invented modern cinema all by himself and his family name was Zukor. He had no interest in movies and just wanted to make money… according to the article.

Well, I didn’t believe that. Nobody goes into the movie biz just to make money and I’m pretty sure if he’d invented cinema on his own I’d know more about him. So I searched some more to flesh out my knowledge.

He Founded Paramount Pictures

Adolph was born in Hungary in 1873 and he lived to be over 100 years old. After both his parents died, he left Europe for America in 1891. He arrived with nothing, but by 1903 he’d gone from apprentice furrier to wealthy businessman making money in the trade of fur.

Adolph truly represented the American Dream ™. From nothing to wealth by the age of 30. And he hadn’t even invented cinema yet.

It was at this point that he met another successful furrier called Marcus Loew. They became lifelong friends. And (to cut a long story short) Adolph went on to found Paramount, while Marcus founded MGM Studios. They also became lifelong friends.

Cutting a short story long

Adolph’s movie success was probably down to 2 insights: 1) movies should be driven by the stars in them and 2) audiences would have an appetite for feature films with proper stories.

In 1903, Adolph and business opened a penny entertainment arcade. There were phonographs, peep shows, punching bags, and target practice games – all a penny each. It was named “Automatic Vaudeville” (as opposed to live Vaudeville like theatre).

While it was no more than a sideshow in business terms, Adolph found himself fascinated by the arcade. He’d been hooked by showbiz (of a kind) and soon after quit the fur trade.

Adolph decided to show motion pictures on the top floor of Automatic Vaudeville. Each film was only 15 minutes long and they were seen as brief amusement, like peep shows and punch bags. But Adolph managed to inflate the entry ticket price using a clever marketing trick…

“Most of our customers didn’t know what moving pictures were and were used to paying one cent, not five. So we put in a wonderful glass staircase. Under the glass was a metal trough of running water, like a waterfall, with red, green, and blue lights shining through. We called it Crystal Hall, and people paid their five cents mainly on account of the staircase, not the movies. It was a big success.”

A Lesson in Marketing

So, while I was lying in bed on a Sunday morning reading articles on one of the founders of Hollywood, the origins of that town struck me as a useful reminder. Adolph and his colleagues managed to charge 5 times more for a cinema ticket simply by adding an impressive staircase. In other words, he did something different to attract people’s attention.

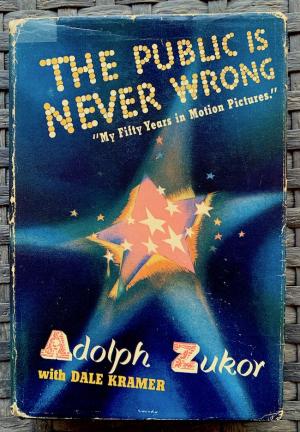

He also paid huge attention to the audience. His autobiography was even titled The Public Is Never Wrong “My 50 Years in Motion Pictures”.

“In the Crystal Hall it was my custom to take a seat about six rows from the front. … I spent a good deal of time watching the faces of the audience, even turning around to do so. … A movie audience is very sensitive. With a little experience I could see, hear, and “feel” the reaction to each melodrama and comedy. Boredom was registered – even without comments or groans – as clearly as laughter demonstrated pleasure.” Adolph Zukor, The Public Is Never Wrong

“Feature” Films

Adolph had a hunch that audiences would love watching longer films, using stories from books or plays. But these films just weren’t around at the time. However, he did not give up on his ambition.

“In 1911, I made up my mind definitely to take big plays and celebrities of the stage and put them on the screen.” Adolph Zukor.

He also said, “It occurred to me that if we could take a novel or a play and put it on the screen, the people would be interested. We should get not only the casual passersby but people leaving their homes, going out in search of amusement.”

He then bought a French silent film called Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth (1912) starring the famous French actress Sarah Bernhardt. It was 40 minutes long. Compared to the 15 minute novelty stuff, this was an historical epic by comparison.

It was at this point that Adolph decided to move into movie production. But he knew nothing about making movies so he spent some time observing successful filmmakers like – Edwin S. Porter and D. W. Griffith – at work. By the summer of 1913, his company had produced five feature films and distributed them to USA and Europe.

Epic Cinema

Well, we know what happened – he was right. But does this sound like a guy who wasn’t interested in the movies and just wanted to make money. Hmm, no.

Yes, he was an extremely smart businessman who had all the right hunches about movies before most others. But he clearly had a deep passion for movies and stories and showbiz. I mean, the crystal staircase invention shows he had a great instinct for theatre.

Adolph’s company went on to produce Cecil B. DeMille’s epic The Ten Commandments (1923), the most expensive movie ever made up to that time at $2 million ($29 million today). In the making, they used 2,500 actors, 3,000 animals and 55,000 feet of lumber for set construction. The movie made huge profits.

But reading that made me wonder what Adolph would’ve thought about CGI driven movies dominating box offices today. Does knowing something was made in box of silicone somehow devalue it in the audience’s mind? Is the reason Christopher Nolan is the only big budget filmmaker making his own stories for $200m down to his understanding of that too?

Anyway, Adolph was a man who understood what it took to get people out of their houses to seek entertainment. And it wasn’t just what was on the screen. And he wasn’t just a furrier turned film producer, either.

Adolph’s company owned hundreds of cinemas and built many of them. They introduced triumphal arches, grand staircases, uniformed ushers, pipe organs and orchestras. He was involved in (and owned) the entire process, from script to theatre – so he understood it completely.

Why is this relevant today?

A few days ago, YouTube sent me a video about a thing called “drop shipping”. I’d never heard of it before. Turns out, you find products cheaply on platforms like Alibaba and Aliexpress, create a Shopify site and re-sell these items for a profit. What you add is marketing.

Well, it’s the crystal staircase all over again, isn’t it? Where Adolph made 5 times more for each ticket because he had the best marketing gimmick. And, you know, then went onto invent feature films and produce epic historical dramas.

I think, as filmmakers, we’re often focused almost 100% on the art of filmmaking. We’re interested in what our stories mean to ourselves, when we might be better off showing an interest in what our stories mean to an audience. Not only that, but we rarely think beyond the final cut of our movie. Marketing is for marketers and perhaps (we think) “beneath” us as artists.

Please Like and Subscribe

OK, so you have your film on Amazon Prime, YouTube or Vimeo but where’s your crystal staircase? I know one thing, saying “Please watch my film, like and subscribe” just won’t cut it. If you’re having to ask people to watch your film (for free) you’re in trouble.

Adolph Zukor didn’t ask anyone to watch his films. Instead, he quietly observed audiences and worked out what entertained or moved them. He also noticed if they got bored or switched off.

My point in all this is to remember where we came from and how we started. It’s almost 100 years since a Hungarian American produced The Ten Commandments. The media world today is unrecognisable, compared to how it was then. But, ultimately, we still need that crystal staircase.

If you liked this article, please subscribe to our newsletter… 😉

Join our weekly newsletter featuring inspiring stories, no-budget filmmaking tips and comprehensive equipment reviews to help you turn your film projects into reality!

Simon Horrocks

Simon Horrocks is a screenwriter & filmmaker. His debut feature THIRD CONTACT was shot on a consumer camcorder and premiered at the BFI IMAX in 2013. His shot-on-smartphones sci-fi series SILENT EYE featured on Amazon Prime. He now runs a popular Patreon page which offers online courses for beginners, customised tips and more: www.patreon.com/SilentEye